Kenneth Levy

I'd like to begin with a bit of historical perspective. There was a time when music was not considered appropriate to the general college curriculum. And here I must say I'm speaking from the point of view of the liberal arts college and the humanities student. The first flowering of liberal arts teaching of music came only in the 1920's and 30's. There were three patriarchal figures, George Dickinson at Vassar, Doc Davison at Harvard, and Roy Welch at Princeton. They were all born in the 1880's and they began their careers as practical musicians. As was the fashion, they completed their education in France or Germany. But they were strong enough intellectually to impress their hard-nosed academic colleagues, and so they carved out a place for music in the liberal arts curriculum of the big universities. I remember Welch in his 60's. He was a charismatic silver-haired figure. He assumed Wagnerian airs. He walked around the campus in an opera cloak. This greatly impressed the undergraduates at the time; perhaps it still would. He was also a shrewd and passionate advocate for generalist music. Many of the thousands of young whom he captivated with the first exposure to the "Eroica" Symphony or the Tannhäuser Overture went on to an active involvement with musical philanthropies in their corporate and community associations.

Each of us here today will have a different way of introducing music to non-musicians and to some extent each of us is dealing with a different clientele. When any of you go out into the field, you're likely to meet different situations of this kind. But I think we all have common goals. One of these is simply human, to expand musical horizons, to expose our students to values that will enrich their later lives. One of the most satisfying things is being approached years later by someone telling you how much music has meant to him because of such a course once taken in college. But there is another significant goal and this has been well put by Bob Freeman. It is, and I quote, "to help strengthen music's national infrastructure, preparing as such courses inevitably should fair numbers of those who will ultimately become board members of operatic, chamber music and symphonic societies all over the United States." As we view the state of music today, this is of critical importance. There may be no other area of our professional activity where we can make a more significant contribution to the well being of the art that we all cherish.

Our approaches are bound to reflect our particular or personal talents, interests and personalities. Concerning my own approach let me begin with a general point. I do not regard as important the use of any particular repertory such as the privileged canon of western musical masterworks. In my teaching I do use western art and popular music of the past three centuries. Those are what I use principally. But I think results no less effective are obtainable with other musics, with popular or ethnic musics from all times and places. Whatever the particular body of material, I think the essential thing is that the student become involved in what I call active listening. The learning of facts and dates, historical sequences, and the like is completely unimportant. The music itself must be the focus, and it is important that we make that music not simply wash through the ears as sensory experience. The critical faculties, the intellectual faculties must somehow be engaged. There should be an awareness of what the composer's options were and an attempt to assess the particular options chosen. The profitable attitude is why does a given material appear at a particular point. What else might have been chosen; would it have been better if something else had been chosen? Of course, it is hard to do that with Beethoven and Bach. But one must raise the question nonetheless.

Now let me briefly set out four points that are the cornerstones of my approach. The first concerns the use of music notation. In order to reach non-musicians I feel that no more than the barest minimum of musical notation should be used. No reading of full scores, no piano reductions, no line scores. This may sound drastic. Reading the score, hearing the music from it is basic to our own experience as musicians. Shouldn't we teach others to make those same associations between sight and sound? Then, of course, we can test them on what they can pick out in the score. It is a comfortable arrangement. It flatters the student. But I think it is deceptive. In the very brief teaching time available—12 weeks, 3 hours a week; sometimes they come, sometimes they don't. There is inadequate time to learn music through notation. We can't really get them to hear much of a score, and short of that kind of musician's hearing, the notation only stands in the way of the active listening that one should want. Composers intend their creations to be heard, and their meanings are communicated not to the eyes of the ticket- and record-buying publics but directly to their ears. What I propose is dealing in the composer's own terms, using the audible bridge, not the visual one. For the amateur, the score is only a detour that slows down the process of understanding—it is a turn away from active involvement with the music. The novice tries to catch the brass rings of notation but the music flies by, and in that breathless process the novice barely manages to hold on. The real sense of the music is lost.

My second point concerns major-minor tonality. Tonality is the mainspring of most art music in the west. Yet often enough the best we do with it in general teaching is to oblige reluctant students to memorize some abstract information about the circle of fifths and the key signatures. I think we should aim higher and to get in closer to the actual experience of the music. Some of the energies that are salvaged from the busy work of score reading can be redirected into serious attempts at hearing the keys as different positions in musical space and experiencing the dynamics of their relationships. I think it is possible for notational illiterates to sense in the first part of the sonata form the vital displacement in a modulation from tonic to first contrasting key. In a development, one can follow the adventurous exploration of different keys and then, when a recapitulation affirms the primacy of an initial tonic, the fulfillment as heard sound and long-term memory come together. These are not easy things to grasp but they are basic to tonal structures as we understand them, and we owe it to our students to encourage them to understand the concepts that they involve. This results in a more substantial penetration of the music than any breathless following of the score.

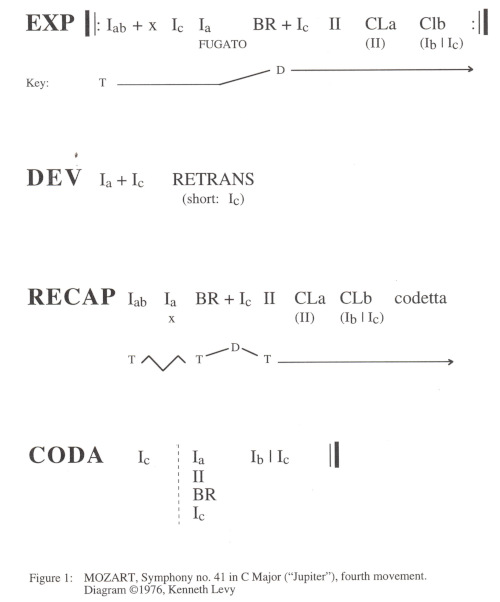

My third point has to do with listening diagrams. Without the score one needs some other visual correlative to help the listener along. There are various systems in use. One of them shows the main themes in music notation and then tries to make them vivid with purple prose. Another one describes some obvious sonic events, signposts in words, and then measures them out with the second hand of a watch. I think this stopwatch, big bang approach takes the student even further from the musical experience than the purple prose. The kind of diagramming I myself use again in the very limited situation that I have faced for many years as a teacher is represented in the example below, a diagram representing the last movement of Mozart's "Jupiter" Symphony:

This diagram gives an overview of what might be heard, a representation of what a moderately perceptive listener might grasp after three or four attentive hearings. The point is to give the listener a spacious architectural plan, an orientation where not only the twigs but something of the forest can be seen. My diagrams have their bits of musical notation but these are kept to a minimum, just the tags of some of the chief materials. What is essential about the exercise should take place as the student, through repeated hearings, relates the heard patterns to the larger plan. Each diagram tries to represent something of the multi-level musical experience, and there are melodic, motivic, dynamic and tonal features to be seen. Each diagram may be different from the other because each is going to reflect the kind of musical situation that it is trying in its ineffectual way to describe. So there will be different features, just as the pieces themselves differ. But in the process, what one hopes the student will learn is how the composer addresses usually conventional paradigms and also about the quality of a composer's imagination in transcending those paradigms. One thing to be said in favor of an arrangement like this—and this is one thing that's more or less imposed on me in my own teaching—is that by way of equipment my method calls for nothing more than the single sheet of diagram and a personal cassette player or Walkman CD. Thus, we deal with the absolute minimum of technology. It is cheap, it's direct, they've all got it, and in one sense this solves a whole lot of problems.

My final point concerns class assignments and testing, which are, let's face it, very important parts of the learning process. This raises another aspect of the listening diagrams, one I consider quite important. The diagrams are not to be taken as authoritative or correct. I tell this to each student from the very start: "this is not firmament; this is not scripture." These things are fallible, they are weak, they are working formulations that in the mind of the student should remain open to clarification and improvement as musical sense reveals itself through repeated hearings. Thus, instead of passively accepting the diagram, the student should be encouraged actively to improve on it. The diagrams are by their nature imperfect representations of a musical work, and the student's first job is to come to grips with them as they are. But then the next and more important task is to think about how the diagrams might be changed.

The best challenge for the students is to produce their own diagrams, sometimes using unknown examples that are assigned without any guide. This gives plenty of freedom. With an interested group of students this can make for very lively discussion. It solves much of the agony facing students in class; if you can involve them, you've really done at least 50 percent of the work. And the whole process also serves very well for both homework assignments and for tests.