Matthew Hoch, baritone, and Jeremy Samolesky, piano. Discover Auburn Lecture Series, Ralph Brown Draughan Library, Auburn University, Auburn, AL. April 5, 2018.

Transcription

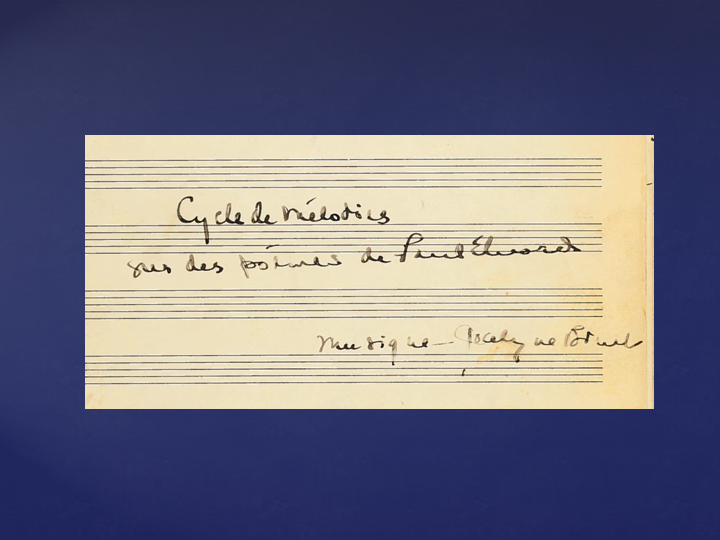

Matthew Hoch: Hello there. My name is Matthew Hoch. I am Associate Professor of Voice at Auburn University, and today I would like to talk to you about a recent research project of mine that culminated in the publication of a forgotten song cycle that had never been published before: Jocelyne Binet’s Cycle de Mélodies sur des poèmes de Paul Éluard. Over the next twenty minutes or so, I will take you on my entire editorial journey from start to finish.

The goals of my presentation today are fivefold. First, I will introduce Jocelyne Binet to you, and talk about her compositions. I will also discuss the origins and circumstances surrounding the Cycle de Mélodies. I will reveal the excavation process for resurrecting the cycle, including some manuscript, engraving, and copyright issues that I ran into. I will analyze and discuss each of the six songs from both poetic and musical perspectives, and finally, I will share with you a complete performance of this work that I recorded in January of 2018.

Jocelyne Binet was born in a small town in Québec on September 27, 1923. She studied composition and piano at the Université de Montréal, where she earned two degrees. After graduating, she studied at the Paris Conservatoire from 1948 to 1951. It is almost certain that she met Pierre Bernac and Gérard Souzay during this time. Pierre Bernac was the most famous teacher of the French mélodie during the twentieth century, and he is remembered today for his book, The Interpretation of French Song, which is on the shelves of many voice teachers’ studios. Gérard Souzay went on to become one of the most important interpreters of the French mélodie during the twentieth century.

Binet returned to Canada in 1951, where she taught composition at the École de musique Vincent d’Indy in Montréal and later at Laval Université in Québec City. She died in Québec City on January 12, 1968. She never married and had no children.

Binet’s compositional output is interesting when you consider that most of her works were written during her student years. She has three orchestral works written during this time, two chamber pieces—a trio written for violin, cello, and piano; and a suite for flute, piano, and strings—and some vocal works: the Petite Suite Vocale and Nocturne. The one exception is the Cycle de Mélodies, which was written much later than the other works.

Binet’s compositional output slowed considerably after she returned from Paris in 1951. From this time forward, her primary identity was that of an academic and professor of composition.

Cycle de Mélodies is one of Binet’s only compositions that was written during her time at the École de musique Vincent-d’Indy (1951-1957). It is likely that these pieces were performed at this institution during Gérard Souzay’s visit to Montréal during his 1955 North American tour, and it is also likely that Souzay’s presence and willingness to perform them inspired Binet’s renewed compositional activity.

Souzay was not a singer who had a habit working with a variety of pianists. He had very few collaborative partners over the course of his career. His regular accompanist until 1954 was French pianist Jacqueline Robin-Bonneau. Her reluctance to travel internationally resulted in Souzay pairing with American pianist Dalton Baldwin beginning in 1954. Baldwin would remain Souzay’s accompanist and life partner until Souzay’s death in 2004.

Therefore, Dalton Baldwin was most likely the pianist who played the 1955 performance, although it is possible that Binet—a pianist herself—played the first performance. Attempts to correspond with Dalton Baldwin (now 87 years old) to clarify the matter were not successful.

This project has some interesting origins. I have long been a Gérard Souzay enthusiast, and I noticed this work listed as a piece of new music performed by Souzay in 1955, the same year the piece was written (as dated on manuscript). This performance was most likely the world premiere.

This was interesting because Souzay was not particularly known as a performer of new music. Especially compared to his contemporary Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, relatively few composers wrote works with Souzay’s voice in mind. Notable exceptions include Jacques Leguerney (many songs and cycles), Arthur Honegger (La danse des morts, 1938), Igor Stravinsky (Canticum Sacrum, 1955), and Ned Rorem (War Scenes, 1969). Mid-career, Souzay’s interest in performing new music seems to wane considerably.

After discovering this title in Souzay’s catalog, I began searching for the score. My extensive personal Gérard Souzay discography and online database searches (OCLC and others) revealed that the piece had never been recorded. This was significant, because Souzay was a prolific recording artist. Glendower Jones initially had never heard of the piece. This is also significant, because Glendower knows everything. He later confirmed that it had never been published.

Liza Weisbrod, music librarian at Auburn University, helped the author track down the Jocelyne Binet archives, which are currently housed in the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). French-language request was then submitted to BAnQ inquiring about the manuscript of the Cycle de Mélodies.

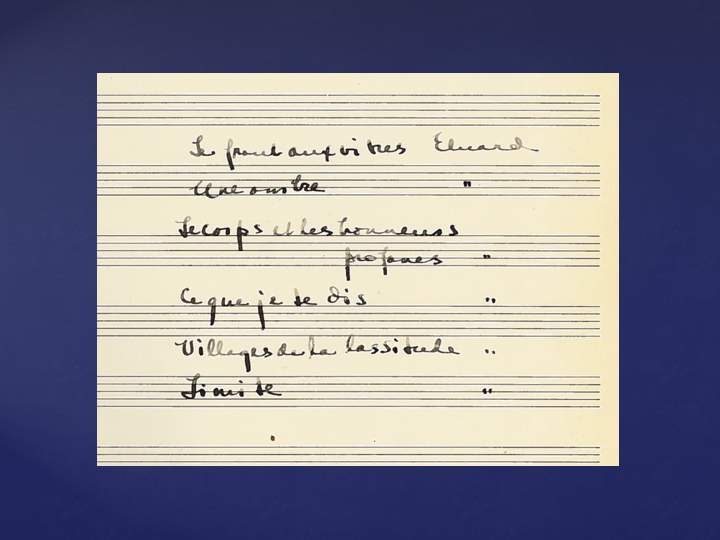

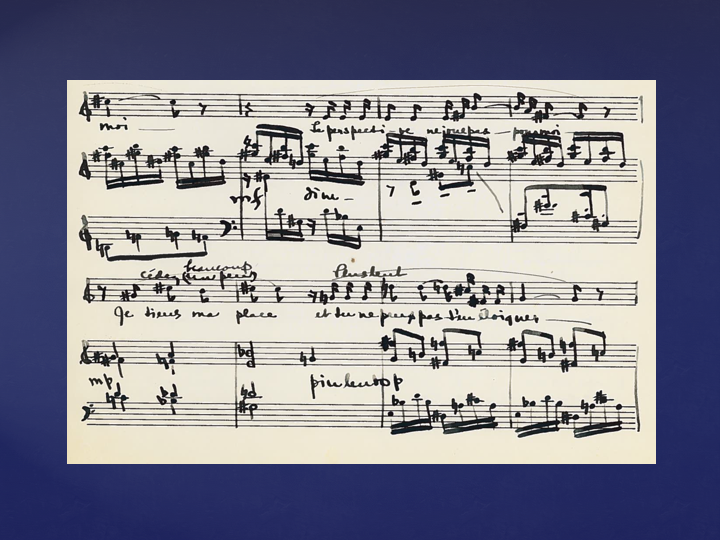

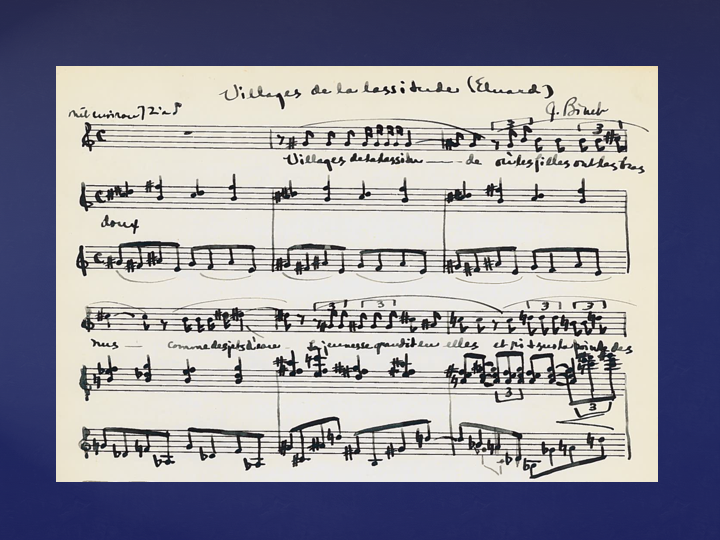

A period of waiting then began. Initially, I heard nothing back from the library, until one day the manuscript arrived. In September of 2016, PDF scans of the complete manuscript are emailed to the author. It was a handwritten manuscript in Binet’s own handwriting. There were ten pages total: one cover page, one contents listing, and eight pages of music. While the music is somewhat clear, much of the French is maddeningly indecipherable. The total number of songs, according to both the contents page and the music itself, is six—not seven as indicated in Historica Canada and other online databases that catalog Binet’s works. This determination was an important discovery.

The next several slides show pages from Binet’s original manuscript. This slide shows the title page, that was signed by Binet herself.

This next slide shows the contents listing, which lists the six songs that comprise Binet’s cycle.

Here, we have a page from Song IV of the cycle.

And here is another excerpt from Song V.

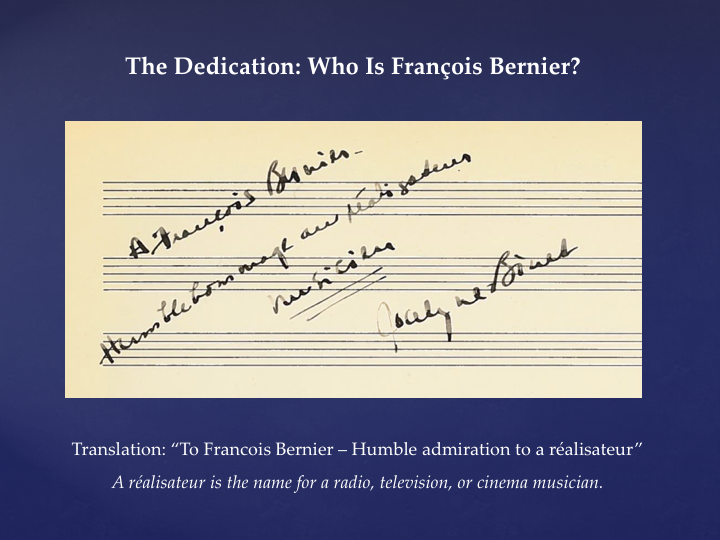

The dedication of the cycle was also something of a mystery. Who is François Bernier, to whom the cycle is dedicated? In the front of the score, Binet writes (in French): “To François Bernier—Humble admiration to a réalisateur.” A réalisateur is the name for a radio, television, or cinema musician. This clue began my journey to discover who François Bernier was.

The initial challenge was deciphering the correct spelling of the name. Initially it was believed to be “Bunils,” but assistance from professors Amanda Johnston of the University of Mississippi and Jessica McCormack of Indiana University–South Bend, as well as comparison with other handwriting in the manuscript, eventually shifted to the correct “Bernier,” a far more common Québécois name.

The most famous musical Berniers were a prominent family of musicians from Québec City during the first half of the twentieth century. The patriarch of the family—and the most well-known Bernier—was the cellist and music critic Maurice Bernier. After much initial frustration, it was discovered that there is a variant in the spelling of the dedicatee’s first name: “François” versus “Françoys.” The latter spelling yielded an entry in Historica Canada and other online databases.

And thus, an identification was made. François Bernier was a French-Canadian pianist, composer, radio producer, arts administrator, and music educator. He was the son of the Québécois cellist and music critic Maurice Bernier. He was an active conductor and producer for CBC radio in the 1950s and early 1960s; served as music director of the Montréal Festivals from 1956 to 1960. Bernier was also general director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Québec from 1960 to 1966 and the orchestra’s music director from 1966 to 1968

Only four years younger than Jocelyne Binet and also spending his entire career in Montréal and Québec City, it is certain that he and Binet were at least acquaintances with one another and probably friends as well. Both were living in Montréal in 1955, which is also when Bernier was in his prime as a réalisateur.

When one examines Binet’s score, certain stylistic observations can be made. First, the range and tessitura of the Cycle de Mélodies strongly suggests that Binet was writing with Souzay’s baryton voice in mind. The style of the cycle owes much to Francis Poulenc and Jacques Legerney, both of whom were writing in a similar style during this time period.

Like Poulenc and Leguerney, Binet’s songs are not unified by any sort of tonal or pitch-class cohesion. Motives and ostinatos support freely chromatic melodic lines that are governed more by the natural declamation of Éluard’s poetry. Form is dictated by punctuated stanzas and shifts in poetic meaning. Double inflections in the same vertical sonority indicate Binet’s preoccupation with the linear nature of lines, as opposed to the spelling out of chords and vertical harmony in the traditional sense.

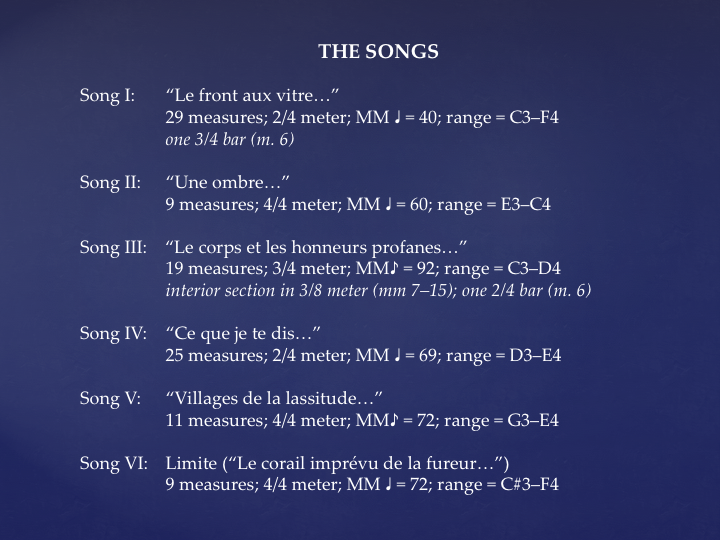

Also like Poulenc, Éluard’s poems are drawn from disparate collections with little thematic unity between them. Cohesion is brought about through the composer’s overall organization, stationing of content, and motivic ideas as opposed to unification of text and imagery. All songs are rather short, ranging from only nine measures (in Songs II and VI) to twenty-nine measures (in Song I). Erratic tessituras (similar to Poulenc’s songs written for Bernac’s baryton-Martin voice) are also a hallmark of the cycle.

This chart shows musical features from all six songs. As you can see, most of the songs are very short, ranging from only nine measures to twenty-nine measures in length. Also somewhat limited in range, the entire range of the cycle only goes from C#3 to F4, an octave and a fourth in total range.

This work has several other interesting features. First, Binet was very specific about tempi with clear metronome markings for each song. The manuscript, however, reveals that she changed her mind on some tempi, perhaps as a result of rehearsals with Souzay. The engraved score represents Binet’s final decisions with regard to tempo.

There are no key signatures; melodic and harmonic content are not rooted in any sort of tonal or pitch-class system. There are, however, motives that recur, forming ostinato-like underpinnings for individual songs. The Cycle de Mélodies does not require a large vocal range and does not exploit Souzay’s robust lower register. Song II has the smallest range—a minor sixth—whereas Song I has the largest: an octave and a fourth.

The cycle begins and ends on an open perfect fifth. Songs I and VI also share thematic content and have almost identical ranges: C3–F4 versus C#3–F4. Songs II through V all begin and end in dissonance, emphasizing second and seventh chords. Major and minor triads are consistently avoided.

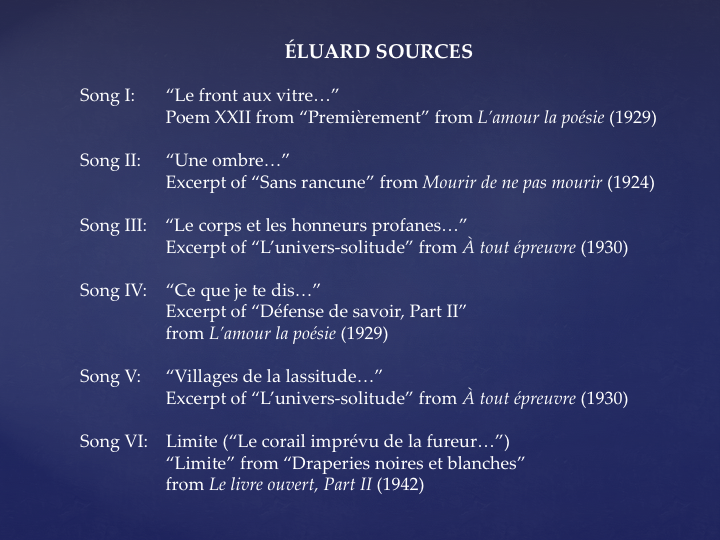

The poetry of the Cycle de Mélodies is worthy of discussion. Binet’s work gathers together six poems by Paul Éluard, the post-surrealist French poet who was also frequently set by Poulenc (along with fellow post-surrealist Guillaume Apollinaire). Like Poulenc, Binet did not seek poetic unity in her selection of texts. They come from five different poetic sources, and only two of the six poems are complete; the other four are excerpts from longer poems.

Because Binet’s handwriting was so challenging to read, tracking down the six original Éluard poems was by far the most time-consuming part of my research. This would have been next-to-impossible before the advent of online poetry archives and databases.

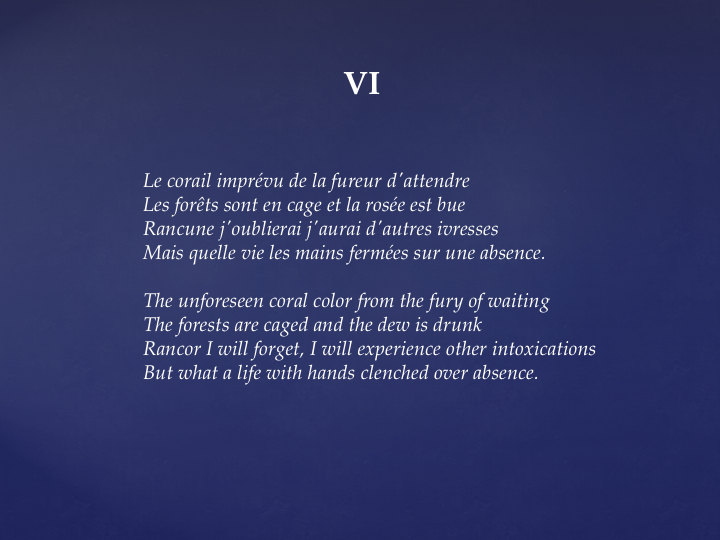

Five of the six poems come from early Éluard collections. Only “Limite” (the final poem) is from a late collection. This poem is also in a completely different style than the other five, favoring the classic twelve-syllable alexandrine as opposed to Éluard’s more typical vers libre. It is possible that this poem was chosen for its final word—“absence”—which is set on an open fifth, thus concluding the cycle as it began.

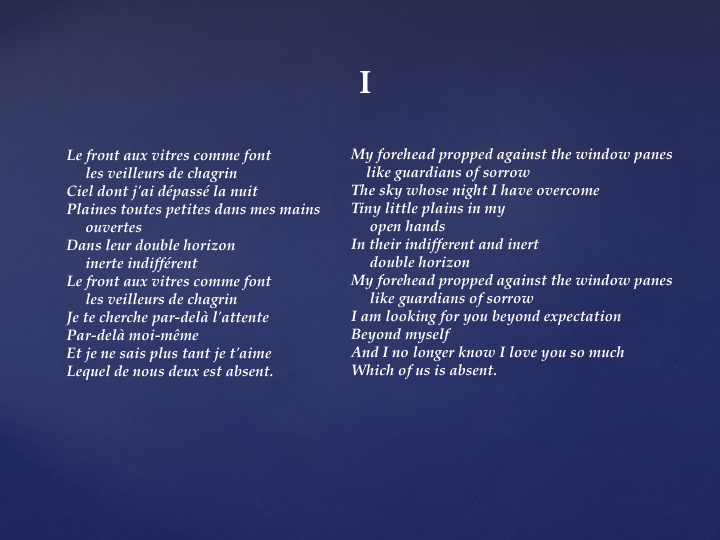

This slide consists of a chart that reveals the original sources for the six poems that Binet selected. Over the course of the next six slides, you will hear a complete performance of the work, which I recorded in January of 2018 with Auburn University pianist Jeremy Samolesky. On each slide, you will see a translation that was written by myself and Dr. Margaret Marshall. I invite you to listen to this performance while following along with the text.

[13:42 – Matthew Hoch performs Song I: “Le front aux vitres”]

[15:12 – Matthew Hoch performs Song II: “Une ombre”]

[16:00 – Matthew Hoch performs Song III: “Le corps et les honneurs profanes”]

[17:03 – Matthew Hoch performs Song IV: “Ce que je te dis”]

[17:53 – Matthew Hoch performs Song V: “Villages de la lassitude”]

[19:29 – Matthew Hoch performs Song VI: “Limite”]

Some other research should also be mentioned. In March of 2017, I made an in-person visit to the Binet archives in Québec. The visit was interesting, but yielded no substantial new information. In 2018, I published the fully engraved Cycle de Mélodies with Glendower Jones at Classical Vocal Reprints. The year 2018 is significant, because it is the year that the work entered the public domain—50 years after Binet’s death. The publication includes a critical essay and facsimile of the original manuscript.

A forthcoming article about my journey has been submitted to the Journal of Singing for possible publication. Future research includes continued exploration of Binet’s oeuvre with emphasis on her other vocal works. Another research goal is to consider this work alongside other twentieth-century French mélodies via the intersection of French poetic meter with rhythmic, metric, and other temporal aspects of selected works by Poulenc and Leguerney.

If you are interested in purchasing the engraved score of the Cycle de Mélodies, you can do so by visiting the website of Classical Vocal Reprints. The cover of the work is pictured here.

I would like to express my gratitude to several institutions and individuals who made this project possible. I would first like to thank the librarians and archivists at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). I would also like to thank Glendower Jones of Classical Vocal Reprints for publishing the score. Liza Weisbrod, music librarian at Auburn University, and Evelyne Bornier, associate professor of French, were also invaluable. James Doyle engraved the manuscript, and Amanda Johnston and Jessica McCormack helped me decipher certain pages of the handwritten French passages. I am grateful to Margaret Marshall for her help with French translation, and finally, I would like to thank Anna Hersey, associate editor of lectures, performances, and lecture-recitals for the College Music Symposium, for archiving this work.

While the research for this project was mostly my own, I am indebted to these three resources, which proved to be invaluable during the course of my research.

This concludes my presentation for today, but if you would like to discuss this work further, or would like to ask me any questions—I would be more than happy to hear from you. My contact information is on this slide. Thank you so much for joining me today, and I hope that you will enjoy listening to Jocelyne Binet’s Cycle de Mélodies and exploring the score. I hope that this work receives many performances in the coming decades.

Matthew Hoch is Associate Professor of Voice at Auburn University. He holds the BM from Ithaca College, MM from the Hartt School, and the DMA from the New England Conservatory. Dr. Hoch is the 2016 winner of the Van L. Lawrence Fellowship, awarded jointly by the Voice Foundation and NATS. matthewhoch.com

Matthew Hoch is Associate Professor of Voice at Auburn University. He holds the BM from Ithaca College, MM from the Hartt School, and the DMA from the New England Conservatory. Dr. Hoch is the 2016 winner of the Van L. Lawrence Fellowship, awarded jointly by the Voice Foundation and NATS. matthewhoch.com