Education In Music for All Individuals is Every Musician's Responsibility

C. Tayloe Harding, Jr.

Why must education in music for all individuals be the responsibility of every musician? The reason is that maximizing education in music for all individuals is the best way to insure the establishment of a culture of living in and through music to improve the Iives of all Americans. When we Live Through Music—that is, when we play an instrument or listen carefully—many aspects of our lives are improved. Studies reveal how helpful the action of participating in music is to many of our daily mental and physical functions. The more we participate actively in music, the greater the benefit to us.

Living In Music involves a deeper, more profound connection. It concerns a conscious awareness of that place within us where music's effect is personal and emotional. When we Live in Music we experience music's deep meanings, and this experience inspires new outlooks on life.

Thus, when we Live Through Music and Live in Music—as opposed to being passive listeners and simply having music around us—we make ourselves and, by extension, our society, a richer, more thoughtful, and more sensitive place.

The Two Tasks

Our first task is to create more environments where more people can Live Through Music. Only by creating more opportunities for engagement—through every available means, including schools, community centers, and religious centers—and staffing them with competent musicians, can we begin to offer people the opportunity to Live Through Music.

As our first task is accomplished, the second task—providing for everyone the opportunity to Live in Music—will follow. Providing opportunities for fulfillment of the most personal longings for aesthetic experience will make our fellow humans happier and their lives more rewarding.

Thus, using our music and its power to establish a culture of living through and living in music must be our priority. For us in the music professoriate this is imperative given the condition of the culture of our country and our hopes for its improvement.

What We Can Do Ourselves

(1) As college teachers we can renew our commitment to the non-professional music student and the general college student. Both populations merit our vigorous attention and best teaching efforts.

(2) As practitioners of music, we can affect the general population directly. We must develop ideas on how to conduct greater outreach to and engagement with our communities. No other group of musicians can play such a variety of roles. We are composers, pedormers, educators, and researchers, and we can share our knowledge with those around us.

(3) We must help non-professional music students learn to love more music and learn to love the music they already love even more. Specific methodologies that "leverage" their existing love for their current musics must be explored. Love Leverage Listening is one example.

(4) We must develop a better understanding of why music affects us as it does, why this is important to us, and how we can help non-musicians comprehend, hear, and feel this, too. We can affect change with respect to the role music plays in our society, our happiness, and our ability to get along with one another by increasing our fellow human's knowledge and experience with music (the through and the in).

What We Can Do for our Students

(1) We must adopt new, additional ways to educate our professional students in music. Our profession's primary goal with our professional music studens has been to train and develop their talent. This is not enough. We must teach our students about their responsibilities as educators. We must teach this as well—and with as much integrity, enthusiasm, and vigor—as we teach all other aspects of the curriculum. We must make educating through and in music a part of basic musicianship in our professional music curricula, right along with theoretical knowledge, aural skill, performance and ensembles skill, knowledge of history and literature, and all else that has an honored place in music study. We must create new courses and experiences for our professional music students that teach skills and knowledge for inspiring people to seek opportunities to Live through Music and to want to Live in Music. We must teach our students what they must do on behalf of music.

(2) We can educate our professional music students to understand the needs of the general population and their responsibility to meet those needs as future teacher-practitioners. As college teachers we can make it possible for every music student to develop the tools to live up to their educational responsibilities. We can insure that future generations of music students know that Education In Music for All Individuals Is Every Musician's Responsibility.

(3) We must expand our approach to outreach and engagement. We have hoped that "music would speak for itself," that performances of our music would inspire others to love it. We have not given sufficient thought to what it takes to get people beyond our students to love our music. Although music does "speak for itself," it may be speaking a language that is incomprehensible to our culture. Given the din of voices trying so hard to be heard, to have their fifteen minutes of fame, and to find a niche in people's lives, it is easy to understand why music of aesthetic depth has been marginalized to the fringe, even at times in the culture life of our own campuses.

(4) We must make a case for the power of music to affect positively people's lives. We have hoped that staying focused on superior talent development would be enough to sustain our art. We now live with the consequences of this passive attitude toward outreach and engagement. We must begin to train our students to be systematic advocates on behalf of music. In fact, Living In and Living Through music can save the lives of Americans, too. Part of the reason music is one of the first subjects cut from school curricula when financial times are hard is because it is commonly held that music is not "life and death" or "critical to survival" like math, reading, writing, and science. But not experiencing music is certain aesthetic death, while experiencing music is life improving and life altering. That music can change, improve, and save lives is what should be commonly held. We must train our students to be articulate advocates.

(5) We must continue to develop and improve our music teacher training programs for students and recertifiers who will elect to teach in elementary and secondary schools by including content knowledge on the meaning of Living Through and Living In music.

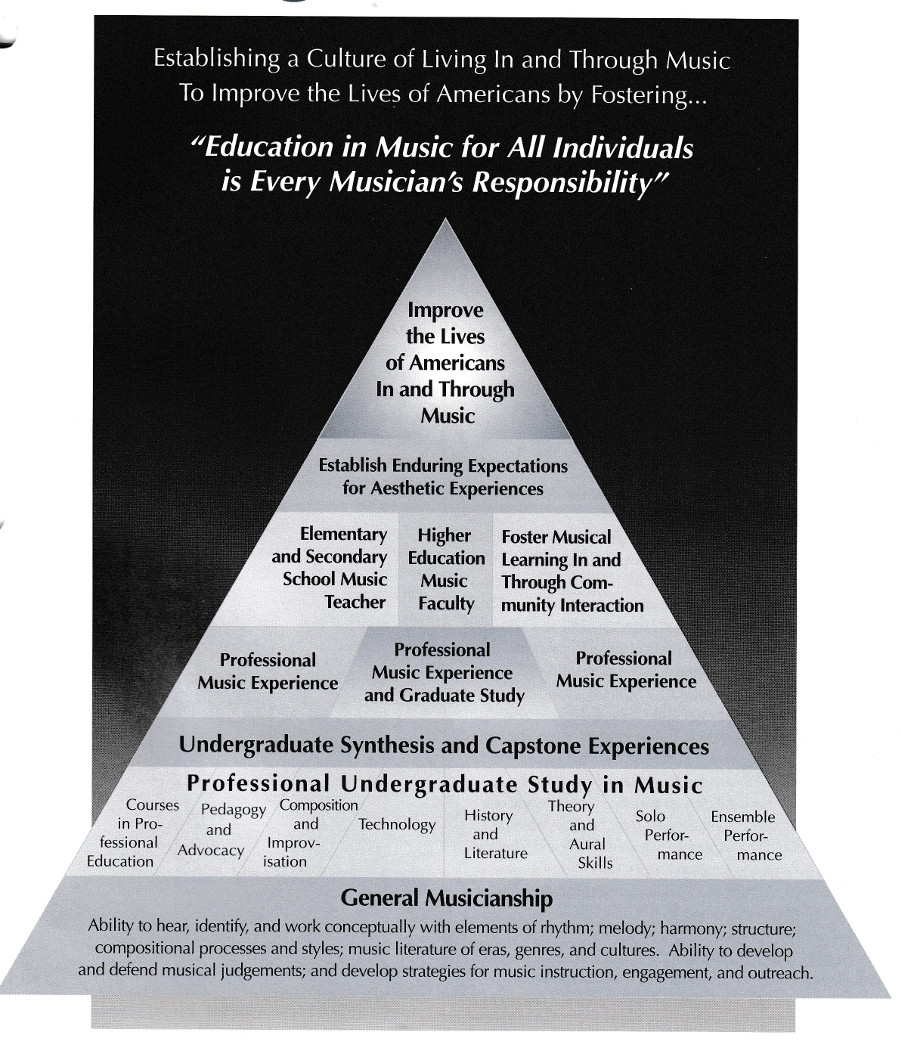

On the adjacent page is a pyramid entitled Establishing a Culture of Living Through and Living in Music to Improve the Lives of Americans. Inspired by the idea that we must see all teaching of music as equally impoftant activity, instead of "up into college" or "down into the public schools," this pyramid outlines what a typical professional musician will do from the beginning of his/her professional training. Notice that, at the bottom, I propose language that solidifies education in music as a musicianship activity. Meeting our goal's first objective, accepting and practicing that Education in Music for All Individuals is Every Musician's Responsibility, is the focus of this pyramid's contents.

How Do We Do It?

The best way to do this is for all of us, as professional musicians, to: (1) realize that even the best music in schools and traditional music education can only do some of it, (2) accept our responsibility to educate individuals in and through music, and finally (3) convert our acceptance of the responsibility into a meeting of the responsibility. This is what the Quebec Plenary Sessions will be about. We hope to collect all sorts of ideas from all types of music sub-discipline specialists. Some of these ideas may be immediately doable and some may require greater thought, resources, training, or time.

We invite all CMS members to be part of this important dialogue.